Historical Background

After the end of WW2, Slovenia became a part of the new state of Yugoslavia, (a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement,) which set its own independent path to socialism between the capitalist West (US) and communist East (Soviet Union). The new Yugoslavian social political system, was combination of ‘market-socialism’ and ‘workers’ self-management socialism’, based on the concepts of social ownership and social equality. The post-war reconstruction began with the nationalization of private property and the simultaneous “construction” of the new state.

The planners began to search for and to develop new urban and architectural solutions for the organisation of housing development through combining their expressions and interventions with Modernist and Functionalist principles while taking into account the regional historical and social context. The aim was the improved quality of living for the general public, but the solutions had to be rational and economical.

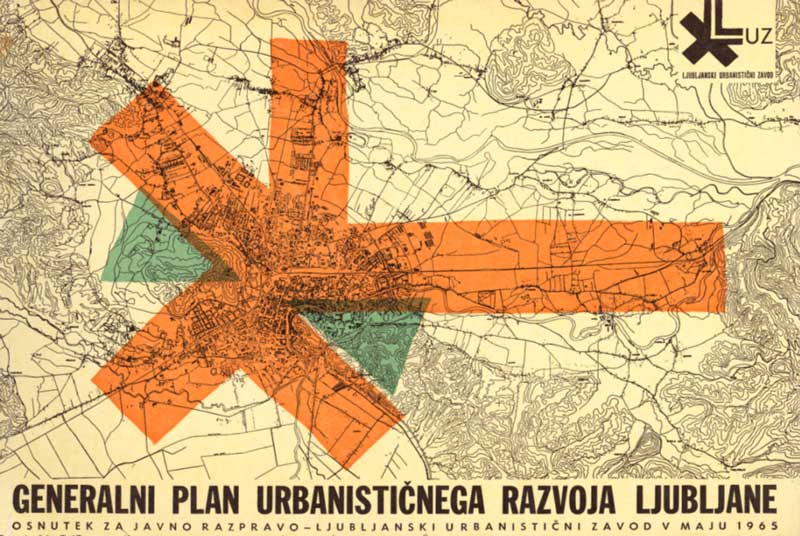

General Urban Plan of Ljubljana

In Ljubljana, the key projects of renovation and city development were taken on by the young generation of architects led by architect and professor Edvard Ravnikar, student of Jože Plečnik, who worked in Le Corbusier’s studio shortly before WW2.

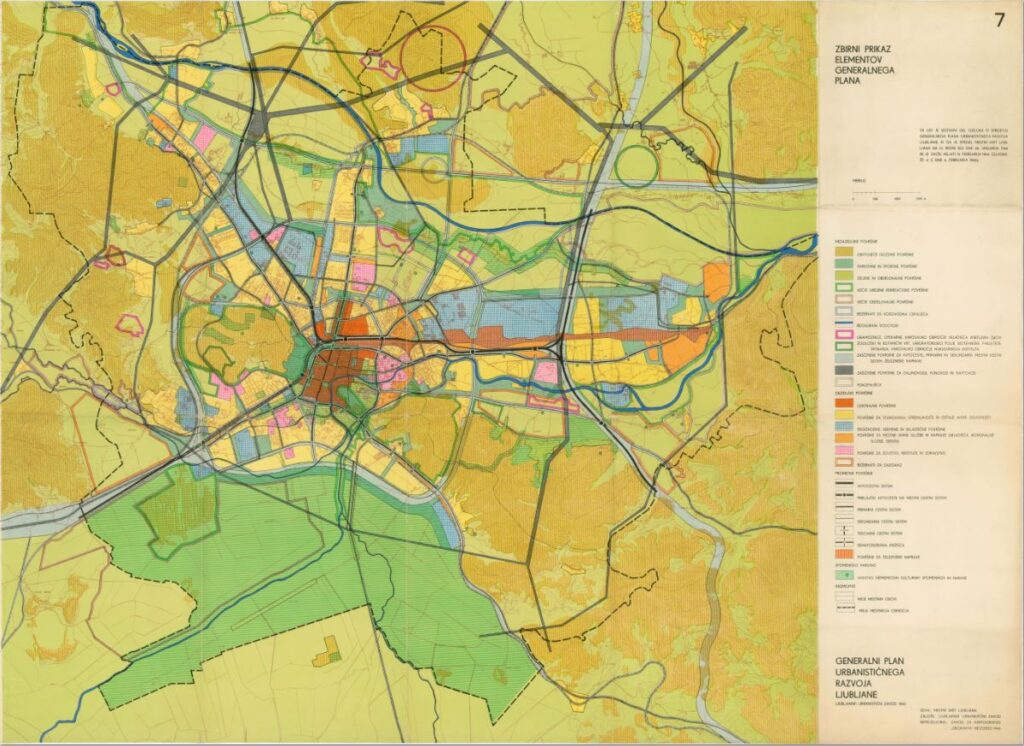

In 1955, in the seminar of prof. Ravnikar the study of a radial development of city Ljubljana was produced, which was based on local geographical features but also included the latest international breakthroughs in urban planning (especially Scandinavian: the primary reference was the neighbourhood Vallingby, a satellite settlement in the suburbs of Stockholm).

The study proposed a series of tall residential developments along the city arteries while retaining long tongues of green areas between the radials extending all the way to the city centre.

That model became the basis for the General Urban Plan of Ljubljana adopted in 1965, the first comprehensive urban document of the city after the WW2, which devided the city into urban zones and defined neighbourhood unit as the fundamental organising principle of urban planning policy.

In the same year, also a housing reform was implemented, which triggered the beginning of the construction of housing for the market. Further development of the city was carried out with an intensive construction of housing estates until the end of the 80s.

Ideal Neighbourhood

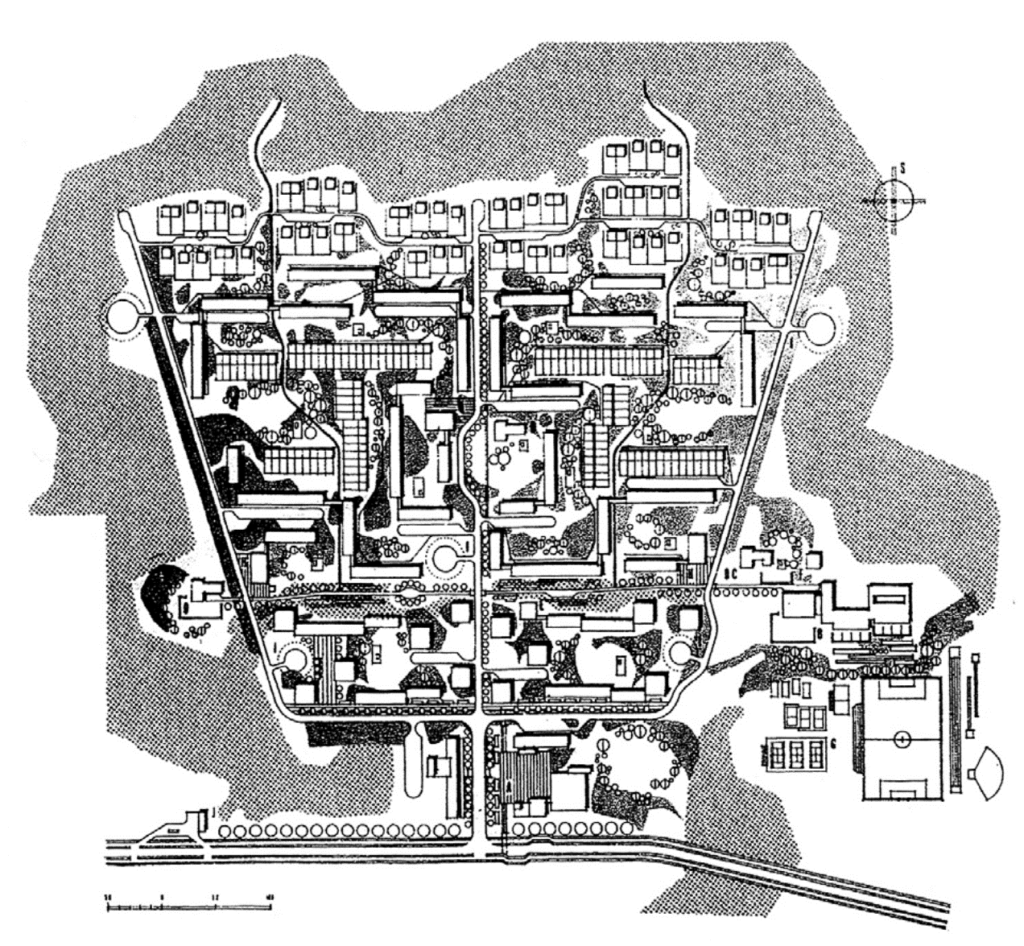

The residential areas were conceived as the sociological and physical groupings – neighbourhoods. The concluded autonomous territorial units enabled a better organisation of a city’s spatial development.

The basic model of the neighbourhood unit planned on the criteria of pedestrian streets and paths with the primary school in the centre (pioneered by American planner Clarence Perry for the Regional Plan of New York in 1929) was upgraded by organisation of space according to function: residential areas, public areas, transport network, recreational areas and green space. All the functions essential for the everyday life of the inhabitants were planned in the area; these were social, educational, cultural and service programs.

THE IDEAL NEIGHBOURHOOD

This concept was presented as the model of an “ideal neighbourhood” for 5,000 inhabitants at the exhibition “Family and Households” in Zagreb in 1958.

To foster diversity in the population structure, model included different housing typologies, from high-rise apartment buildings to individual houses. The centre of the neighbourhood emphasised by skyscrapers (to build up the identity of the site) was located along the main road on the outer edge of the area with a bus stop nearby. The traffic routes were completely separated from the pedestrian areas, no transit motor traffic was permitted within the estate. Great attention was paid also to creating quality green open spaces in residential areas.

This concept was presented as the model of an “ideal neighbourhood” for 5,000 inhabitants at the exhibition “Family and Households” in Zagreb in 1958.

Neighbourhoods – general description

The creation of residential neighbourhoods in Slovenia in the period from 1960 up until the end of the ’80s included all key principles of the “ideal neighbourhood”, but always implemented in an innovative way, with a great commitment to exploring new housing concepts adapted to the modern lifesyle.

Modernist neighbourhoods in Ljubljana are characterised by strong, distinct, and clear urban and architectural design with good integration in the surrounding space and offering quality living conditions. Instead of constructing compact, unarticulated megastructures (globally widespread practice at that time), a more suitable design of smaller units intertwined with the natural environment were preferred. The final form of buildings was dictated by the use of construction principles, building techniques, materials, and was the result of a carefully elaborated idea and logic of construction.

The creation of high-quality open public spaces in the neighbourhoods’ area was as important as the design of buildings.

New neighbourhoods were meant to offer a decent standard of living for all. Even today they are located near green recreational areas, they feature all contemporary infrastructure, owing to their sitting by the city arteries they have good traffic connections to the city centre and the wider vicinity and good access to public transport.

Map of modernist neighbourhoods in Ljubljana: http://www.mao.si/Upload/file/Modernisticne%20soseske%20v%20Ljubljani.pdf

Weak points of modernist neighbourhoods

Most neighbourhoods weren’t realised in their entirety; until the final realisation, the original projects were changed either in terms of the programme or use of space, mostly because of political or economic pressures. The neighbourhood was treated primarily as an organised unit of residential construction. From the moment when the market principle model was introduced, backed by banks loans and state’s guarantees, the community aspect was not a priority any more. As a result, the accompanying programme of services (stores, post offices, etc.) was not of key importance and was often realised in a much-reduced scope.

The consequences of the compromises between expert solutions and political and economic conditions are felt by the present-day inhabitants of the neighbourhoods daily – a dire lack of parking spaces and a deficiency of public programme. A shortage of spaces for inhabitant interaction is reflected in loosely knit communities and a poorly developed sense of belonging, resulting in the absence of common vision regarding the management and development of the neighbourhoods.

During the last few decades, significant changes of neighbourhoods began. The uncoordinated interventions of individuals on the building’s exteriors and energy efficiency refurbishments, mostly disrespectful to the original architecture, have spoiled the visual appearance of the buildings, threatened architectural authenticity, and eroded the coherence of entire neighbourhoods, which are being transformed into unrecognisable complexes with a ruined identity.

Current situation and the reasons for it

The collapse of Yugoslavia, and Slovenia’s independence in 1991, have led to changes in the political system. The new organisation of Slovene society with the socio-economic system based on private property have greatly influenced the country’s development and has been reflected in the spatial policy and legislation. One of the key privatisation laws, which set the transition from socialism to capitalism, was the Housing Act adopted already in 1991. A direct consequence of the law is the very high fragmentation of ownership in multi-apartment buildings (more than 90% of apartments is in private ownership, there is practically no publicly owned apartments, and consequently, there is considerable lack of apartments for rent), Also, a large number of building managers in a single neighbourhood and still-unsolved disputes regarding ownership of public areas within residential areas are the reason for the current situation of those living environments.

Furthermore, it is also necessary to realize that today’s unenviable state of affairs in neighbourhoods has not been caused by inadequate or outdated “Socialist” urban layouts and architectural concepts, or the social conditions there, but by incomplete executions of programmes envisaged in design projects and problematic, poorly-conceived ways of privatising collective property immediately after Slovenia’s independence.

Spatial legislation and its implementation

The lack of legal and regulatory measures as well as the absence of their implementation plays an essential role in unawareness of the importance of a harmoniously arranged environment, low level of spatial culture, and consequent spatial chaos in Slovenia.

Legislation in the field of construction and spatial interventions is poorly regulated. In particular, the set of interventions in buildings belonging to the category of maintenance for which it is not necessary to obtain a building permit is problematic. Maintenance works include renovation and energy renovation of facades, glazing of balconies and loggias, window replacement, etc., which all have a significant effect on changing the visual appearance of the building and consequently its surroundings. Control of interventions in space for which the acquisition of a building permit is not required is not within the competence of the construction inspection. In the new Building Act (2017) and its subordinate legislation, the provisions remained unchanged despite the constant warnings of the professional public about the devastating consequences of such regulation.

The Housing Act stipulates that the owner may perform maintenance work, changes and improvements on his individual property if this does not impair other parts of the building and does not change the appearance of the building. For violations of this provision, financial penalties are foreseen, but in reality, there is no control over the interventions, nor is anyone exercising sanctions. The new Ljubljana Municipal Spatial Plan defines the conditions for the maintenance of multi-ownership buildings (reconstruction of the facade only in the original colour, glazing of the balconies must be based on a uniform solution for the whole building, window change is permissible only consistent with the determination from the building permit, etc.) Currently, there is no proper control over the fulfilment of these provisions, although it should be carried out by a City Inspection Service. These provisions are generally taken into account only when a municipality is involved in the renovation of the building with financial subsidies.

To summarise, the vague and uncoordinated legislation and, especially, disrespect of laws, absence of control over interventions, together with the lack of sanctions for violations, impart a sense of legality to such acts within the Slovene society.

All this has largelly contributed to today’s miserable image of multi-apartment buildings or neighbourhoods. Individual homeowners pursue their interests and fulfill their wishes and needs, but forget that any intervention on the building envelope is also reflected in the shared space. Improper treatments on the facades result in degraded buildings, and degraded buildings reduce the quality of our shared space.